Tags

Financial Systemic Issues: Booms and Busts - Central Banking and Money - Corporate Governance - Cryptocurrencies - Government and Bureaucracy - Inflation - Long-term Economics - Risk and Uncertainty - Retirement Finance

Financial Markets: Banking - Banking Politics - Housing Finance - Municipal Finance - Sovereign Debt - Student Loans

Categories

Blogs - Books - Op-eds - Letters to the editor - Policy papers and research - Testimony to Congress - Podcasts - Event videos - Media quotes - Poetry

Barron’s LTE (Copy)

Published in Barron’s.

In asking “Is the Federal Reserve Using Overheated Data?” (Up & Down Wall Street, March 11), Randall W. Forsyth did the math: “If the Fed fulfills its own expectations of three [interest rate] hikes this year, it would put its target at 1.25 percent to 1.5 percent.” Let’s call it 1.5 percent at the end of this year. That is still a very low and substantially negative real interest rate. Against the Fed’s own goal of perpetual inflation at 2 percent a year, it is a real rate of negative 0.5 percent. Against the 2.5 percent increase in the consumer price index year over year through January 2017, it is a negative 1 percent real rate.

Although negative real interest rates during a crisis are usual, continuing them for nine years after the crisis ended, as it will be a year from now, serves powerfully to distort asset prices and rob savers.

U.S. banks’ real estate boom could be signaling next crisis

Published in Inside Sources.

Excessive real estate credit is the most common cause of banking booms, busts and collapses, throughout history, right up through the most recent financial crisis and around the world.

The U.S. commercial banking system has gotten much bigger relative to the U.S. economy than it used to be, although there are many fewer banks. The principal source of this growth is that banks have vastly increased their real estate exposure relative to the U.S. economy as a whole. This acceleration in real estate risk has fundamentally changed the nature of the banking system and its systemic risk.

Looking back to 1960, there were in the United States: 13,126 commercial banks and 18,962 depository institutions. By the end of 2016, depositories totaled only 5,913, of which 5,113 were commercial banks. That’s a 69 percent reduction in the number of depository institutions, and a 61 percent reduction in commercial banks.

On the other hand, in 1960, the total assets of the commercial banking system were only $256 billion. Though hard to believe, the entire banking system had total assets of only about one-tenth of today’s JPMorgan-Chase, and only 1.6 percent of today’s banking assets of $15.6 trillion. Citibank — which wasn’t Citibank then, but the dignified First National City Bank of New York — had less than $9 billion in assets. To our minds, now muddled by decades of constant inflation — including a central bank that has formally committed itself to creating perpetual inflation — these all seem like very small numbers.

Instead of measuring in nominal dollars, to see through the fog of long years of inflation, we can measure banking assets consistently relative to the size of the economy, as a percent of annual gross domestic product. The $256 billion of commercial banking assets in 1960 was 47 percent of the $541 billion in GDP.

The increase is striking: by 2016, banking assets had gone from 47 percent to 83 percent of GDP. That is more than a 75 percent increase in the banking system’s size relative to the economy, at the same time the number of banks fell by more than 60 percent. At present, this ratio is close to its all-time bubble peak.

What is driving this growth? It’s not commercial and industrial loans. On the trend, their percent of GDP is flat at 8 percent to 10 percent since 1960. On average, the commercial and industrial loans of the banking system have kept up with the growth of the economy, but not more.

The real driving factor is real estate credit. The commercial banking system’s real estate loans rose relentlessly from 5 percent of GDP in 1960, to more than 26 percent at their bubble peak, and are now at 22.5 percent.

Nor is this the whole real estate story. With the popularization of mortgage securitization, the banking system’s securities portfolio, not only its loan portfolio, shifted to real estate risk. Going back to 1992, the sum of banks’ real estate loans and mortgage-backed securities as a percent of GDP has risen to 32 percent — six times the 1960 level.

In short, the vast bulk of the dramatic increase in the size of the banking system relative to the economy comes from the acceleration of real estate exposure — a rising trend for more than six decades. How can the banks keep doing this? Well, it helps to have your liabilities guaranteed by the government, both explicitly through deposit insurance and implicitly through bailouts and central banking.

Should the banking system keep getting bigger relative to the economy, and should this increase continue overwhelmingly to reflect real estate risk? That is a dubious proposition. As Columbia University’s Charles Calomiris has written (in a not-yet-published paper): “The unprecedented pandemic of financial system collapses over the last four decades around the world is largely a story of real estate booms and busts. Real estate is central to systemic risk.”

Very true. But as Calomiris notes, the Financial Stability Oversight Board, set up as part of the Dodd-Frank Act to oversee the U.S. financial system, “seems to be uninterested.”

The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 defined a bank as an institution that accepts demand deposits and makes commercial loans. Neither part of this old definition still touches on the main point. A bank now is for the most part an institution that makes real estate loans and funds them with government-guaranteed liabilities.

This banking evolution poses a huge systemic question: How do you deal with a banking system whose risks are concentrated in real estate prices and leverage? To this question we are, as yet, without an answer. Do the supposed systemic thinkers at the Financial Stability Oversight Council even understand the magnitude of the historic shift in risk? Maybe a future FSOC with new members will do better.

What is the actual collateral for a mortgage loan?

Published in Real Clear Markets.

“Economics and finance are like going to the dog races,” my friend Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute is fond of saying. “Stand in the same place and the dogs will come around again.” So they will.

U.S. financial markets produced sequential bubbles – first in tech stocks in the 1990s and then in houses in the 2000s.

“What is the collateral for a home mortgage loan?” I like to ask audiences of mortgage lenders. Of course, they say, “the house,” so I am pleased to tell them that is the wrong answer. The correct answer is the price of the house. My next question is, “How much can a price change?” Ponder that. The correct answer is that prices, having no independent, objective existence, can change a lot more than you think. They can go up a lot more than you think probable, and they can go down a lot more than you think possible. And they can do first one and then the other.

This is notably displayed by the asset price behavior in both the tech stock and housing bubbles. As the dogs raced around again, they made a remarkably symmetrical round trip in prices.

Graph 1 shows the symmetrical round trip of the notorious “irrational exuberance” in dot-com equities, followed by unexuberance. It displays the NASDAQ stock index expressed in constant dollars.

Now consider houses. Graph 2 shows the Case-Shiller U.S. national house price index expressed in constant dollars. Quite a similar pattern of going up a lot and then going down as much.

The mortgage lending excesses essential to the housing bubble reflected, in part, a mania of politicians to drive up the U.S. homeownership rate. The pols discovered, so they thought, how to do this: make more bad loans—only they called them, “creative loans.” The homeownership rate did rise significantly—and then went back down to exactly where it was before. Another instructive symmetrical round trip, as shown in Graph 3.

The first symmetrical up and down played out in the course of three years, the second in 12 years, the third in two decades. Much longer patterns are possible. Graph 4 shows the amazing six-decade symmetry in U.S. long-term interest rates.

Is there magic or determinism in this symmetry? Well, perhaps the persistence of underlying fundamental trends and the regression to them shows through, as does the reminder of how very much prices can change. In the fourth graph, we also see the dangerous power of fiat currency-issuing central banks to drive prices to extremes.

Unfortunately, graphs of the past do not tell us what is coming next, no matter how many of them economists and analysts may draw. But they do usefully remind us of the frequent vanity of human hopes and political schemes.

George Kaufman: 57 years of banking changes and ideas

Published by the R Street Institute.

57 Years of Banking Changes and Ideas

Remarks at the Dinner in Honor of Professor George Kaufman’s Retirement

Nov. 17, 2016

It is a great pleasure to be able to add these reflections to our proceedings in honor of George Kaufman upon his retirement.

We begin a quick trip through American financial history during George’s career with this quotation:

The past 100 years of American banking have been characterized by periods of remarkably rapid change.

This observation is from 56 years ago, from the 1960 Report of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. It was true then, and is true now.

The year before that, in 1959, the young George Kaufman walked into the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago to begin his career. Needless to say, the “periods of remarkably rapid change” in American banking continued as his career progressed.

In 1960, there were in the United States: 13,126 commercial banks, 5,320 savings and loans, and 516 mutual savings banks. Those institutional differences then seemed much more important than they do now—these groups all had their own trade associations, for example. Together they made in 1960 a total of 18,962 depository institutions. As we all know, this number is now just over 6,000 and continues to fall. But that is still a lot of banks!

Two questions which would occur to the participants in this dinner, although doubtless never to ordinary citizens, are: When did the United States have its maximum number of banks? And how many banks was that? (I will not call on Charlie Calomiris here, because he might know.[1]) The answers are the year 1921 and it was 31,076 commercial banks. In addition, there were more than 8,000 savings and loans.

Coming back to 1960, the total assets of the aggregate commercial banking system were $256 billion—about one-tenth of the assets of today’s JPMorgan-Chase. That was 48 percent of the 1960 gross domestic product of $535 billion. The total assets of the prestigious 1959 Citibank—which wasn’t “Citibank” in those days, but the First National City Bank of New York—were $8.3 billion, or about 0.3 percent of the current JPMorgan.

Closer to home, I found the 1958 numbers for the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Co. of Chicago. That then-very-conservative balance sheet had total assets of $2.9 billion—today’s size of a large community bank.

A truly striking statistic is that in 1960, non-interest-bearing demand deposits at national banks were equal to about 60 percent of their total banking assets—something unimaginable now.

Also in 1960, there were still outstanding $55 million of national bank notes—currency issued by individual banks. The Federal Reserve had on its balance sheet $279 million of silver certificates. These were the paper money, as you will recall, which the U.S. Treasury promised to redeem for a silver dollar—something quite different from the fiat currency we have come to know so well. Well, perhaps not so different after all, because in the first decade of George’s career, the government decided it would renege on its commitment to pay in silver.

A roomful of economists will not have failed to notice that in all the numbers I have cited, I have used nominal dollars. There are two reasons for this:

Rhetorical fun

To remind us that George’s long career has involved unceasing, endemic inflation.

Indeed, this has progressed to the point where the Federal Reserve has formally committed itself to perpetual inflation. Such a development in Federal Reserve ideology would have greatly shocked and surprised the chairman of the Federal Reserve for the first decade of George’s career, William McChesney Martin, who called inflation “a thief in the night.”

Speaking of the Fed, George’s first career decade also included the Credit Crunch of 1966 and his second began with the Credit Crunch of 1969. Those were the days of the notorious “Reg Q,” under which the Fed set maximum interest rates on deposits and, in so doing, caused the painful crunches.

Did the Fed know what the right interest rate was in 1966 or 1969?

Nope.

Does the Fed know what the right interest rate is now?

Nope.

We move into the 1970s. They started with a world historical event, at least as far as finance goes: the default by the United States on its Bretton Woods commitment to redeem dollars held by foreign governments for gold. Announcing this decision in August 1971, President Richard Nixon blamed the problem on “international money speculators.” The real proximate cause was French President Charles de Gaulle’s financial good sense of preferring gold to overvalued dollars.

In the wake of the end of Bretton Woods, the 1970s brought us the worldwide system of fiat currencies and floating exchange rates. This system has experienced a remarkable series of debt and currency crises in the ensuing years.

Speaking of debt crises, the default by Puerto Rico was discussed this afternoon. On Page 15 of George’s 38-page curriculum vitae, we find that in 1975, George was involved in the government finances of Puerto Rico and was a consultant to Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank. This bank is now utterly insolvent, as is the whole government of Puerto Rico. However, I do not think it would be fair to attribute this to George’s 1975 advice!

In 1976, George was working in the U.S. Treasury Department. Here were the 10 largest banks in the United States, in order, in 1976:

Bank of America (that is, the one is San Francisco)

Citibank

Chase Manhattan

Manufacturers Hanover

Morgan Guaranty

Continental Illinois

Chemical Bank

Bankers Trust

First National Bank of Chicago

Security Pacific

Of these 10, only two still exist as independent companies. They are Chemical Bank, which became JPMorgan-Chase, and Citibank, which has in the meantime been bailed out three times.

In the next decade, in 1981, George became the John F. Smith Professor of Finance and Economics here at Loyola University of Chicago, the chair he has held ever since, also serving as the director of the Center for Financial and Policy Studies.

Soon after George got his chair, the financial disasters of the 1980s came raining down. I assert, however, that this is correlation, not causation.

On a Friday in August 1982, then-Fed Chairman Paul Volcker called his counterpart at the Bank of Japan and announced that “The American banking system might not last until Monday!” Over the years 1982-1992, the notable total of 2,808 U.S. financial institutions failed. That is an average of 255 failures per year over those 11 years, or five failures a week. As many of us remember, the decade included the crisis of huge defaults on LDC—or “less developed country,” as we then said—debts; the collapse of the savings and loan industry; the bursting of the oil price bubble, which among other things, took down every big bank in Texas; the collapse of a bubble in farmland, which broke the Farm Credit System; and finally, a massive commercial real estate bust.

These 1980s disasters, which George studied and wrote about with much insight, call to mind James Grant’s vivid comment about the time: “Progress is cumulative in science and engineering but cyclical in finance. … In technology, banking has almost never looked back, [but] this progress has paid scant dividends in judgment. Surrounded by computer terminals, bankers in the 1980s committed some of the greatest howlers in financial history.”

The 1980s included, of course, the 1984 collapse of Continental Illinois Bank. Defending the ensuing bailout, then-Comptroller of the Currency Todd Conover introduced the memorable term “too big to fail.” The problem of “too big to fail” became an important theme in George’s work.

In the midst of these 1980s financial debacles, in 1986, George led the creation of the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee. In its operation through 2015, the committee published 362 mostly trenchant and provocative policy statements. No. 362 was still dealing with “too big to fail.”

For the year 1987, George published a summary of this “dramatic year in U.S. banking and finance,” which included these observations: that “rates on long-term Treasury bonds stood at 9 ½%”; that “some 185 commercial banks failed during the year”; that “the drain on the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation was so great that the corporation ran out of reserves and had to be recapitalized by Congress”; and that “Alan Greenspan replaced Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve,” while “M. Danny Wall [became] chairman of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board.”

Remember the Federal Home Loan Bank Board? Those of us here may, but hardly anybody else does. For Danny Wall, being made head of it in 1987 was like being made captain of the Titanic after it had already hit the iceberg. In contrast, Alan Greenspan rose to worldwide stardom and became “The Maestro”—until he wasn’t.

In the 1990s, George and the Shadow Committee were very influential in shaping FDICIA—the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991, which put into statute the theory of prompt corrective action. The decade later brought a series of international financial crises, starting with the frantic bailout of Mexico in 1994.

In the next decade, the fifth of George’s career, came—as we all know too well—the massive housing and housing-finance bubble, bust and shrivel of the 2000s. Reflecting on prompt corrective action in light of those experiences, my conclusion is that it’s a pretty good theory, but financial exuberance makes it hard to practice.

The exuberance of the 2000s was defended as rational by many ex ante, then denounced as irrational ex post. In the aftermath of the 2007-09 crisis, I chaired panel of which George was a member. He gave this wonderful concluding comment:

Everybody knows Santayana’s saying that those who fail to study the past are condemned to repeat it. In finance, those who do study the past are condemned to recognize the patterns they see developing, and then repeat them anyway!

Now here we are, near the end of 2016. I believe we are probably closer to the next crisis than to the last one. It seems to me we need a Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee Roman Numeral II to get to work on it.

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Let us raise our glasses to George Kaufman and 57 years of achievement, acute insights, scholarly contributions, policy guidance and professional leadership, all accompanied by a lively wit.

To George!

[1] The next morning, Charlie told me that he did know

What Dow 20,000 looks like in inflation-adjusted terms

Published by the R Street Institute.

The Dow Jones industrial average closing Jan. 25 at more than 20,000 inspired big, top of the fold front-page headlines in both the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times (although the story was on Page 14 of The Washington Post). The Journal and FT both ran long-term graphs of the DJIA, but both were in nominal dollars. In nominal dollars, the 100-year history looks like Graph 1—the DJIA is 211 times its Dec. 31, 1916, level.

This history includes two world wars, a Great Depression, several other wars, the great inflation of the 1970s, numerous financial crises, both domestic and international, booms and recessions, amazing innovations, unending political debating and 18 U.S. presidents (10 Republicans and eight Democrats). Through all this, there has been, up until yesterday, an average annual nominal price increase of 5.5 percent in the DJIA.

Using nominal dollars makes the graphs rhetorically more impressive, but ignores that, for much of that long history, the Federal Reserve and the government have been busily depreciating the dollar. A dollar now is worth 4.8 percent of what it was 100 years ago, or about 5 cents in end-of-1916 dollars. To rightly understand the returns, we have to adjust for a lot of inflation when we look at history.

Graph 2 shows 100 years of the DJIA in inflation-adjusted terms, stated in end-of-1916 dollars:

Average annual inflation over these 100 years is 3.1 percent. Adjusting for this, and measuring in constant end-of-1916 dollars, 20,069 on the DJIA becomes 964. Compared to a level of 95 as of Dec. 31, 1916, the DJIA in real terms has increased about 10 times. Still very impressive, but quite different from the nominal picture. The average annual real price increase of the DJIA is 2.3 percent for the 100 years up to yesterday.

Growth rates of 2 percent, let alone 3 percent, extended over a century do remarkable things.

Borrowers and speculators benefit at savers’ expense

Published in the Financial Times.

As your report “Fed balance sheet moves up agenda” makes clear (Jan. 19), the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing experiment is still buying bonds and mortgage securities eight years after the crisis ended and five years after U.S. house prices bottomed. Why? What hath the Fed wrought?

It has helped out the government by seriously reducing the cost of financing federal deficits; it has allocated huge resources to its favoured uses of government spending and rapid inflation of house prices; and it has expropriated the wealth of savers by running years of negative real interest rates. Far from it being the case that “all boats were lifted,” I calculate, using long-run average real interest rates, that since 2008, the Fed has purloined about $2 trillion from conservative savers and given it to borrowers and leveraged speculators. The biggest borrower of all, and thus the biggest beneficiary, is of course the government itself, of which the Fed is such a useful part.

The Federal Reserve is the bank most in need of a stress test

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Do you know a bank that is leveraged at more than 100:1-to be exact, with assets of 111 times its equity? You do: it’s the Federal Reserve.

The consolidated Federal Reserves banks had total assets of $4.47 trillion as of Dec. 14, 2016, compared to total capital of merely $40.4 billion, or less than 1 percent of assets-actually, 0.9 percent.

The largest Federal Reserve Bank by far, New York, sports $2.47 trillion in total assets and only $13 billion in total capital, for leverage of a pretty remarkable 190 times and a capital ratio of 0.53 percent.

The Fed enjoys imposing stress tests on everybody else. What if we give the Fed a stress test? The interest rate risk of the Fed is similar to a 1980s savings-and-loan – lots of long-term, fixed rate assets, with short funding. So let’s apply a simple and standard interest rate stress test. Suppose long-term interest rates rise by 2 percent, to a historically more normal level. What happens to the Fed?

Well, the Fed now owns $4.4 trillion of long-term, fixed-rate assets and unamortized premium paid. It does not disclose the duration of this massive position, but let’s say it’s five years (it could be longer). If interest rates rise by 2 percent, the market value loss to the Fed is approximately 5 times 2 percent or 10 percent of the $4.4 trillion position. That would be an economic loss of $440 billion. That is 11 times the Fed’s total capital.

It seems highly likely that the Federal Reserve System, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in particular, would then be hugely insolvent on a mark-to-market basis. Stress test score: F.

Defenders of the Fed confidently claim that it doesn’t matter if the Fed is insolvent. Maybe they are right. If they are, the Fed should have no hesitation at all in publishing the mark to market of its giant securities portfolio, the way the Swiss central bank is required to do. To the Fed Board of Governors: How about it?

The housing bubble renewed?

Published by the R Street Institute.

Average U.S. house prices are back over their 2006 bubble top, as measured by the Case-Shiller Home Price Indices. “Home Prices Recover Ground Lost During Bust” read the Wall Street Journal headline.

But these prices are in nominal dollars, not inflation-adjusted dollars. While the Federal Reserve assures us that inflation is “low,” it tirelessly works to depreciate the dollar. Over the decade since the housing bubble peak, aggregate inflation has been 19 percent, so 2016 dollars are worth 84 cents compared to 2006 dollars.

House prices since 1987 in nominal terms look like this:

In inflation-adjusted terms, the chart is different. Average house prices in real terms are indeed very high, but still 16 percent below their bubble top. They have reached the level of March 2004, when the bubble was well advanced into exuberance, but not yet at its maximum. It had made about 54 percent of its 1999-2006 run.

From 1999 to 2004, real house prices increased at an average rate of 7.2 percent per year. In our renewed house price boom from 2012 to now, real prices have increased at 6.6 percent per year—pretty similar.

All this is depicted in Chart 2:

The Federal Reserve had reduced short-term interest rates to very low levels in 2001 to 2004, which fed the bubble. In 2004, it started to raise them. The house price run up since 2012 has also been fed by extremely low interest rates. Now the Fed must raise rates again and is getting ready to do so. Long-term mortgage interest rates have already increased sharply.

Should being back to 2004 in real terms worry us? Yes.

Household incomes can fall even when everyone’s getting richer

Published by the R Street Institute.

One of the politically hottest statistics right now is median household income, especially its slow growth. But there is a big problem with understanding what this statistic means, since it mixes up two different things: the changing composition of households and changes in incomes. If the makeup of households is altering dramatically, as it has in recent decades, median household income may be a quite misleading number.

For example, it is mathematically possible for everyone’s income to be rising, while the median household income is falling. How is that possible? The paradox is caused by counting by households, when the relationship between individuals and households keeps shifting.

To take the simplest possible case: Consider a population of one household, a married couple, each of whom has an income of $50,000. The median household income is $100,000. Their incomes each rise by 10 percent to $55,000—but they get divorced. Now there are two households. The median household income has become $55,000. The median household income has gone down by 45 percent! Obviously, we have a demographic event, not an income event.

Suppose our married couple stays married with their new household income of $110,000. An immigrant joins the population, making $20,000, which is three or four times his previous income. In this case, the median household income has become $65,000, falling 35 percent! But everybody is better off than they were before.

In what is naturally a more complicated way, just these sorts of major changes have been going on inside the statistics that count income by household. If the composition of households were unchanged, the statistics would be more straightforward. But this is obviously not the case. Until the demographic changes are untangled from the results, it’s not clear what the changes in median household income tell us.

The Fed should be accountable for its results

Published in The Wall Street Journal.

“Vote Brings Uncertainty for Fed” (U.S. News, Nov. 10) says that President-elect Donald Trump might work with Congress to rewrite the laws governing the Fed’s structure. Good idea. It is of course decried by the Federal Reserve as a threat to its independence.

We should hope that the new president does proceed with this project. The Fed needs to be made accountable, as every part of the government should be. The notion that any part of the government, especially one as powerful and dangerous as the Fed, should be granted independence of checks and balances is misguided. Naturally, all bureaucrats resent being subject to the elected representatives of the people, but this doesn’t exempt them from their democratic accountability to the legislature that created them and may uncreate them.

The Fed is still carrying out emergency monetary experimentation seven years after the end of the crisis. It is busy robbing savers to benefit borrowers and leveraged speculators—a political act. It is imperative to figure out how best to make the Fed accountable to the Congress and to correct the evolved imbalance between its power and its accountability.

GDP per-worker vs. GDP per-capita

Published by the R Street Institute.

We have previously compared the growth in real per-capita gross domestic product between the United States and Japan and among the 10 largest advanced economies. Growth in GDP per-capita measures the increase in the average economic well-being in the country, and adjusts gross GDP growth for whether the population is increasing, stable or declining.

We now shift to comparisons of growth in GDP per-worker (more precisely, per employed person). This addresses productivity, rather than overall economic well-being, and adjusts for shifts in the composition of the population among those who are employed. Those are who not employed include, for example, children, full-time students, retired people, those unemployed and looking for work, those unemployed and not looking for work, and those (especially mothers) who do plenty of work in the home, but not as paid employees.

If the overall population is growing, it’s possible for GDP to grow while GDP per-capita does not. Similarly, if there is a shift within the population toward greater workforce participation, GDP per-capita might grow, while GDP per-worker does not. More generally, the growth rates of these measures of economic performance may be quite different.

Table 1 compares the striking slowdown in economic growth between the last half of the 20th century and the first 15 years of the 21st in the growth of real GDP, both per-capita and per-worker. However, the 21st century slowdown, while marked, is less extreme when measured per-worker (1.82 percent to 1.11 percent) than when measured per-capita (2.25 percent to 0.90 percent). In other words, the productivity slowdown is less than the overall economic welfare deceleration. This reflects demographic changes: from 1959 to 2000, the number of workers grew faster than the population as a whole. In the 21st century, it’s grown more slowly.

How does the United States compare to Japan, when measured in growth in real GDP per-worker? Here our data makes us shift to 1960 to 2014, still a more than 50-year run. The relative growth performance of the two countries flips dramatically between the 20th and 21st centuries, although both are significantly slower, as shown in Table 2. Japan will continue to be an interesting case of a very technically advanced, but rapidly aging economy with falling employment and a falling population going forward.

Seemingly small differences in compound growth rates make for big differences if they continue over time. Table 3 shows the multiple of real GDP per-worker over 50 years in the actual second half of the 20th century, compared to a projection for 50 years of the 21st century if the century’s current trends continue. The result is a drop from an aggregate improvement of 2.5 times, to 1.7 times.

Can the growth in real GDP per-worker reaccelerate or not? That is indeed the question.

Letter to Oversight Board of Puerto Rico

Published by the R Street Institute.

In response to your request for public comments on the draft Puerto Rico fiscal plan, I respectfully submit the following thoughts.

An old friend of mine who ran a publishing company was famous for returning manuscripts to hopeful authors with this note written at the top: “OK to revise.” This is my summary view of the draft plan for three reasons:

The recent elections in both Puerto Rico and the United States resulted in changing both administrations. Presumably a new governor and new members of the U.S. Treasury Department will have different or additional positions to explore.

The draft plan entirely sidestepped the critical question of how to approach the debt restructuring obviously required.

The draft plan likewise sidestepped the essential questions about how to address the insolvent public-pension plans of Puerto Rico.

However, parts of the draft plan should, in my opinion, enter into final form and implementation as rapidly as practicable. These are the programs to improve budget controls, financial reporting, rationalization of expenditures, effectiveness of tax collections and, in general, all programs to promote stronger financial management and financial integrity. It seem to me that these should be put into a separate plan document for individual and expedited consideration.

To these essential programs should, in my opinion, be added the creation of a chief financial officer for Puerto Rico, closely modeled on the very successful Office of the Chief Financial Officer of Washington, D.C., which was one of the key reforms under its Financial Control Board in the 1990s.

It would be a pleasure to provide any other information which might be useful.

Yours respectfully,

Alex J. Pollock

Chapter 11 for Social Security?

Published in Barron’s.

In their Other Voices essay, Dudley Kimball and Robert Morgan said that Social Security will be insolvent in 2034.

In the sense of having liabilities vastly greater than assets, it is deeply insolvent today. Social Security really needs the equivalent of a Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization.

Life expectancy for 20-year-old white men in the 1930s was 66—meaning that, on average, he’d get one year of Social Security. Today, a 20-year-old man has a life expectancy of 82.

Social Security has become a complex mix of financial functions. It is partly a welfare program; Kimball and Morgan would make it more so. It is partly a forced savings program with a very low average rate of return. It is partly insurance against outliving your savings. And it is entirely broke in present-value terms, reflecting cash already paid to those who took out much more than they put in.

It is time to draw a line and have a reorganization. Those people who can easily afford it could take substantial haircuts on their future benefits, receiving say 60 cents to 70 cents on the dollar, in exchange for voluntarily opting out of the program. This would make Social Security much less insolvent.

For the other creditors, Congress should step up, write off the Treasury’s loss, put in whatever it takes to pay off the accrued benefits at par, and put Social Security into runoff. To this extent, the government would then have honest, as opposed to dishonest, books. A program designed for the now-irrelevant demographics of the 1930s would slowly liquidate.

Then a sound retirement finance program could be put in place to go forward, based on 21st century demographics. Doubtless, the politics would be interesting. But perhaps starting over offers a better chance than trying to remake the 1930s DC-3 of Social Security into a jumbo jet while it’s flying.

Why current asset prices are dangerously exaggerated

Published in Real Clear Markets.

Over the long term, real per-capita household net worth in the United States has grown at about 2 percent a year. This is a wonderful achievement of the enterprising economy.

In shorter periods, when asset prices get inflated in a bubble, household per-capita wealth appears to rise notably above this long-term pace, but ultimately, bubble asset prices inevitably shrivel. When they do, many commentators claim that a lot of “wealth” been lost by households. It hasn’t, because the apparent wealth was not really there in the first place: it was an illusion of the bubble.

If any very great number of people try to sell out at the bubble prices, the evanescent “wealth” disappears, the bubble deflates and the long-term trend reasserts itself, so the aggregate bubble prices can never be realized. Bubble times reflect what Walter Bagehot so truly wrote in 1873: “All people are most credulous when they are most happy.”

Graph 1 is the record of 1953 to 2016. The temporary illusion of wealth represented by two remarkable bubbles of recent decades is obvious.

We should recall with amused irony that the central bankers formerly congratulated themselves for creating what they credulously called “The Great Moderation.” What they actually presided over was the Era of Great Bubbles: first the Great Overpaying for Tech Stocks in the 1990s, then the Great Overleveraging of Real Estate in the 2000s.

And now? They are congratulating themselves again for innovative or radical monetary actions, including their zero interest rate policy (ZIRP), which expropriates the returns to savers and makes the present values of assets rise. Many observers, including me, think they have by their manipulations inflated new bubbles in stocks, bonds and houses. This has put real household wealth per-capita measured at current asset prices back over its 2 percent growth line, although not as egregiously as in the government-promoted housing bubble of the last decade. We can expect ultimate regression to the trend, as always.

But has the trend shifted? From 1950 to 2000, growth in U.S. real per-capita gross domestic product averaged more than 2 percent per-year. This is consistent with a 2 percent growth in wealth per-capita. But since 2000, real per-capita GDP has grown less than 1 percent per-year. Suppose the stagflationists are right, and this represents not a temporary, but a sustained downshift. Then it would be consistent with real per-capita economic growth to move our trend growth in real net worth per-capita down to 1 percent. Graph 2 shows the possible new trend line, starting in 2000.

If we measure from this new line, the current ZIRP bubble looks much worse; it has reached almost the same magnitude as the infamous housing bubble of a decade ago.

Graph 3 shows the variation from the 2 percent and 1 percent lines, displaying the illusory household wealth effects of the series of bubbles in a different fashion.

The more you believe the stagflationist theory, the more you must conclude that current asset prices are dangerously exaggerated, the greater the bubble you must conclude that the central bank experiments have wrought and the further we have to fall back to the trend.

Growth in per-capita GDP: How does the United States rank?

Published by the R Street Institute.

Growth in gross domestic product after adjustment for inflation (real GDP) is the most frequently reported and discussed economic measure. More important, however, is how people on average are doing from an economic standpoint. This means measuring output per person, or real per-capita GDP, and its growth rate.

How does the United States rank among other countries on this growth measure?

In “Japan vs. the U.S. in Per Capita GDP,” we observed that, for the 15 completed years of the 21st century, there is not much difference between average growth in real per-capita GDP between the United States and Japan—the latter often described as suffering from economic stagnation.

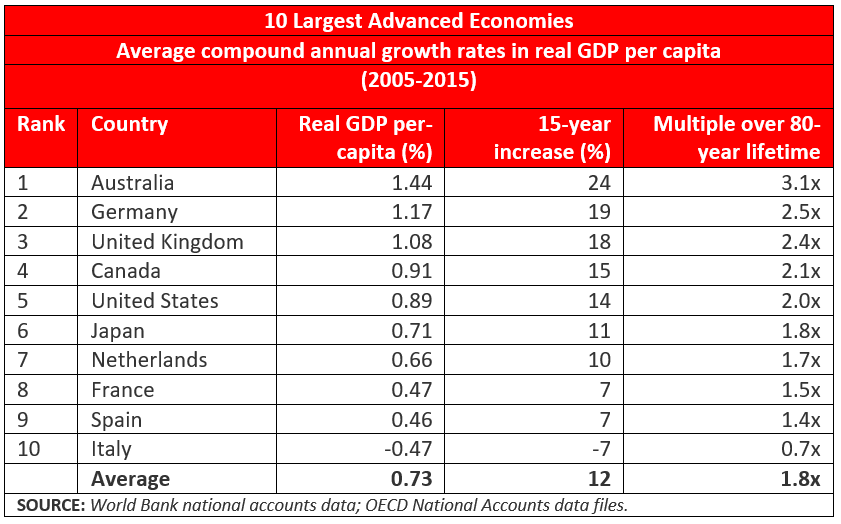

Now we expand our comparison to the 10 largest advanced economies in the world. Here they are, ranked by the average growth rate in real per-capita GDP in this century so far:

Note that the United States and Japan are together right in the middle of the pack, fifth and sixth, respectively, bracketed by Canada and the Netherlands. Three other countries achieved substantially higher real growth rates when measured per person, and three were substantially lower, including Italy, whose growth rate was negative. Among the 10 countries, the average growth rate was 0.73 percent per year, in between the United States and Japan.

The table also shows how much aggregate difference there is as the growth rate compounds for 15 years. At Australia’s leading 1.44 percent average growth rate, aggregate product per person increased by 24 percent in 15 years. The comparable number for the United States is 14 percent. France and Spain are half that at 7 percent and Italy is a 7 percent decrease.

The effects of differences in compound growth rates are always impressive if they continue over a long time.

We calculate what the aggregate increase in average economic well-being would be if the growth rate in real per-capita GDP could be sustained for a lifetime of 80 years. Australians would become, on average, three times better off during their lives; Canadians, Americans and Japanese about twice as well off. Spaniards would be 40 percent better off. In the long view of the millennia of human history, this is very impressive.

Of course, if the growth rate in real per-capita GDP could be 2 percent, these numbers would be much more impressive yet. Then, in an 80-year lifetime, the average economic standard of living would quintuple.

Homeownership Rates: It depends on whether you are married

Published by the R Street Institute.

The attached piece originally appeared in the Autumn 2016 edition of Housing Finance International.

American political rhetoric endlessly repeats that homeownership is part of the “American Dream.” So it is for most people, especially if you are married, as we will see.

As part of promoting this “dream,” the U.S. government has for many years created large subsidies for mortgage borrowing and huge government-sponsored financial institutions to expand mortgage lending. Most notable among these are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which notoriously went broke in 2008 while following the government’s orders to make more so-called “affordable” loans, and survived only thanks to a $189 billion taxpayer bailout.

Fannie and Freddie are still massive operations, featuring a combined $5 trillion in assets (that’s trillion with a “T”), equity capital that is basically zero and utter dependence on the credit of the U.S. Treasury.

Given these massive and extremely expensive efforts, how has the American homeownership rate fared? Let us look back 30 years to 1985, and compare it to 2015. Thus we can go past the housing bubble and collapse of the 2000s, as well as past the financial collapse of the savings and loans in the late 1980s, and observe what has happened over a generation.

Read the rest.

Fed’s mandate is to ensure stable prices

Published in the Financial Times.

Sir, Michael Brownrigg (Letters, Oct. 4) makes a common, but fundamental, mistake in claiming that the Federal Reserve’s mandate includes “low inflation”. To the contrary, in the governing statute, Congress instructs the Fed to pursue “stable prices” not low inflation. Public confusion is understandable, since the Fed endlessly recites the oxymoron that “stable prices” means perpetual inflation (at the rate of 2 percent).

Mr Brownrigg is correct that there is no statutory instruction to the Fed to treat everybody equally. This does not change the egregious fact that the Fed has engineered a massive wealth transfer from savers to borrowers and leveraged speculators. To take a lot of money from some people and give it to others is a quintessentially political act. To whom is the Fed accountable for it?

‘Fin’ versus ‘tech’ in fintech

Published by the R Street Institute.

Financial technology – or “fintech,” in the modern parlance – may be seen as trendy, but computing technology has strongly influenced banking and finance for decades. Its effects include the creation of general-use credit and debit cards, going back to the 1950s, which we now take for granted worldwide; ATMs available any time and almost anywhere, going back to the 1970s; and the data capabilities that make structured mortgage-backed securities possible, going back to the 1980s.

Visa and MasterCard are considered leading fintech companies, which they are. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker once cynically remarked that ATMs were the only real financial innovation of recent times. Meanwhile, MBS vividly display the double potential of innovation, first for growth and then for disaster.

Investment banker J. Christopher Flowers has expressed the view that the current fintech boom will “leave a trail of failed companies in its wake.” Of course it will, just like the hundreds of automobile companies that sprang up a century ago or the myriad dot-com companies that mushroomed in the 1990s. The automobile and the internet were both society-changing innovations and the hundreds of failures are how we discover which are the truly valuable ideas and which aren’t. To paraphrase Friedrich Hayek’s memorable essay, competition is a discovery procedure.

Over time we will find out which innovations are real and which are mere fads. A key distinction in fintech, as in the financial world in general, is between those changes that make transactions faster, cheaper, more mobile and less bothersome (the “tech”), on the one hand; and those that make it easier to make loans and take credit risk (the “fin”), on the other. The former are likely to yield some truly useful innovations; the latter, which require lending people money that you hope they will pay back on time and with interest, is an old and tricky art. It is much easier to fool yourself about whether you are actually improving lending, as compared to technology.

Consider the idea of “lending money over the internet.” The “internet” part may invent something faster, cheaper and easier—just like the ATMs Volcker touts. The “lending money” part may be simply a new name for making bad loans, just as the dark side of MBS turned out to be.

So on one hand, we may have real innovation and progress, and on the other, merely endless cyclical repetition of costly credit mistakes. For example, the fintech firms LendingClub and OnDeck Capital presently find their stock prices about 80 percent down from their highs of less than two years ago, as they learn painful lessons about the “fin” part of fintech.

Nor is this distinction new. As James Grant, the acerbic and colorful chronicler of the foibles of financial markets, wrote in 1992:

In technology, therefore, banking has almost never looked back. On the other hand, this progress has paid scant dividends in judgment. Surrounded by computer terminals, bankers in the 1980s committed some of the greatest howlers in American financial history.

So they did, and more than 2,800 U.S. financial institutions, their growing computer power notwithstanding, failed between 1982 and 1992.

Bankers in the 21st century – avidly using vastly greater technological prowess, supplied with reams of data, running complex computer models to measure and manage (or so they thought) their credit risks – made even more egregious mistakes. As we all know, they created an amazing credit bubble and came close to tanking the entire financial system. Did the technology help them or seduce them?

Mathematicians and physicists – the “rocket scientists,” as they were called – had brought their impressive computer skills to Wall Street to help apply technology to mortgage finance. In the memorable summary of George Mason University’s Tony Sanders, “The rocket scientists built a missile which landed on themselves.” The mistakes were in the “fin” part of this effort, not the “tech” part.

In every financially trendy boom, we hear a lot about “creative” new financial products. A painful example was the homeownership strategy announced with fanfare by the Clinton administration in the 1990s. It called for “creative” mortgages, which turned out to mean mortgages likely to default.

Such products, no matter how much innovative computer technology surrounds and helps deliver them, are not real financial innovations. They are merely new ways to lower credit standards, run up leverage and increase old risks by new names. They are thus illusory financial innovations. As also pointed out by James Grant, science is progressive, but credit is cyclical.

Real innovations turn ideas into institutions which endure over time, various mistakes notwithstanding, as credit cards, ATMs and MBS have. Illusory innovations cyclically blossom and disappear. Both produce uncertainty, and uncertainty means we cannot know the future, period. We will continue to be surprised, positively and negatively, by the effects of financial innovation.

In short, financial markets are always in transition to some new state, but only some of this is progress. The rest is merely cyclical repetition. What is fintech? Doubtless, it is some of both.

Happy birthday, TARP!

Published by the R Street Institute.

Today, Oct. 3, is the eighth anniversary of congressional passage of the act that created the famous or notorious $700 billion bank bailout program in the midst of financial panic of late 2008. In case you have forgotten, TARP stood for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, and the authorizing legislation was the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. An emergency it was, with one failure following fast on another.

Eight years on, when we know that the panic passed, when house prices are booming again, when the stock market is high and life has gone on, it’s hard to recreate psychologically the uncertainty and fear of that period. Memories naturally lose their vividness and then fade altogether, making the next cyclical bust more likely.

The design of TARP originally was to quell the crisis by having the U.S. Treasury buy depreciated mortgage-backed securities from banks, removing these “troubled assets” from private balance sheets and thus giving them “relief.” When this was proposed, it was already clear that it was not going to work. The crisis had created insolvencies, with deficit equity capital. By buying assets from banks so they realized big losses, you were not going to fix their capital. Neither would lending them more money from the Federal Reserve fix their capital: if you are broke, no matter how much more you borrow, you are still broke.

By September 2008, the British government already had decided it had to make equity investments in insolvent banks. This replicated the U.S. experience of the 1930s, when the Reconstruction Finance Corp., originally set up to make loans to troubled banks, realized it had to make equity investments instead, in the form of preferred stock. It also replicated the experience of Japan in the 1990s. As TARP was being debated, it seemed to me that the equity investment model was better than the proposed TARP design, and so it proved to be. The RFC overall made a profit on its bank investments, and so, as it turned out, did TARP.

But what Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson had told Congress in getting the legislation passed was that they were approving a program for buying mortgage securities. However, as Paulson revealed in educational crisis memoir “On the Brink,” even as these arguments were being made:

Ben Bernanke had told me that he thought that solving the crisis would demand more than the illiquid asset purchases we had asked for. In his view, we would have to inject equity capital into financial institutions.

Bernanke was right about that, but Paulson thought “we would sabotage our efforts with Congress if we raised our hands midstream and said we might need to inject equity.” Well, you can’t tell the elected representatives of the people what is really going on. When the act did get passed and signed into law Oct. 3, says Paulson: “I made sure to tell…the team: ‘Figure out a way we can put equity in these companies.’” And so they did.

Shortly thereafter, Paulson reflects, “I began seriously to doubt that our asset-buying program could work. This pained me, as I had sincerely promoted the purchases to Congress and the public as the best solution” and “dropping the asset-buying plan would undermine our credibility.” Instead, TARP proceeded by making equity investments in preferred stock.

By now, the TARP investments in banks are almost entirely liquidated at a profit to the Treasury. The program went on to make losing investments in the bailouts of automobile companies (which equally were bailouts of the United Automobile Workers union) and to spend money not authorized by statute on programs for defaulted mortgages. All in all, Oct. 3 launched a most eventful history.

“I had expected [TARP] to be politically unpopular, but the intensity of the backlash astonished me,” wrote Paulson.

Its birthday is a good time to reflect on TARP and try to decide what you would have done in Secretary Paulson’s place, had you been handed that overwhelming responsibility.

The Credit Crunch of 1966: An instructive 50th anniversary

Published in Real Clear Markets.

It’s the 50th anniversary of the Credit Crunch of 1966, which roiled financial markets in August and September of that year. Group financial memory fades, so if you don’t know or remember that there was such a crunch, searing at the time, you are not alone. Yet it taught an essential lesson, again being relearned right now, 50 years later: the Federal Reserve, and central banks in general, simply do not know what the right interest rate is.

Central to the events of 1966 was that the Federal Reserve set the maximum interest rates that banks could pay on their deposits. This was the Fed’s now long-gone but then critical “Regulation Q” authority, at the time considered an essential part of the banking system.

As of July 1966, the Fed had set the interest-rate ceiling on savings deposits at 4 percent. For so-called “multiple maturity” time deposits (where withdrawal was at the depositor’s notice) it was 4 percent for a minimum maturity of up to 89 days, and 5 percent for 90 days or more. For fixed-maturity date time deposits, the ceiling was 5.5 percent. In September 1966, it dropped to 5 percent, except that deposits of more than $100,000 (that’s $743,000 in 2016 dollars) could still get 5.5 percent.

How did the Fed know those numbers were right? It didn’t, as events demonstrated. Most of the time over the preceding decades, they had set the ceiling over market rates, so it generally hadn’t been an issue.

But in 1966, there was strong credit demand from an extended economic expansion, plus inflationary pressure from the Vietnam War and “Great Society” deficits. Interest rates in the open market went much higher than before. Three-month Treasury bill yields got to 5.59 percent, the federal funds rate to 5.77 percent and commercial paper rates to 6 percent. Market rates on negotiable CDs went over the ceilings. “The prime rate briefly reached the then unheard of level of 6 percent,” wrote economist Albert Wojnilower. A 6 percent prime rate was the highest it had been in more than 30 years.

This time, the Fed refused to raise the ceiling in line with the market, in part reflecting political pressure to limit competition for deposits in order to favor savings-and-loan institutions, which were stuck with long-term mortgages at low fixed rates. Lending long and borrowing short was already dangerous in 1966.

Naturally, in response, people took their money out of both banks and savings and loans and put it into higher-yielding conservative investments, a perfectly sensible thing to do. This process had a cumbersome name at the time: “disintermediation”—a problem created entirely by regulation. Unable to expand their funding, the banks cut back on their loans. The savings and loans cut way back on their mortgage loans. “For most people, residential mortgage money was unobtainable…there was a sharp slump in mortgage loans and housing starts,” wrote The New York Times.

Banks also cut back on their previously expanding investments, notably in municipal bonds. Both banks and thrifts worried about their ability to fund their existing balance sheets. As described by the theoretician of financial crises, Hyman Minsky: “By the end of August, the disorganization in the municipals market, rumors about the solvency and liquidity of savings institutions, and the frantic [funding] efforts by money-center banks generated what can be characterized as a controlled panic.” Not allowed to bid competitive rates for deposits, as the St. Louis Fed’s history of the credit crunch reports: “Banks had never before experienced a large outflow of time deposits.”

So the Fed fixed prices and the result was the credit crunch. Following Wojnilower’s lively account: “Lending to all but the most established and necessitous customers was halted abruptly. Chief executives of leading banks reportedly were humbled to the point of pleading with their counterparts in industry to renew their CDs.” Further, in order to the raise needed funds, there was “the apparent inevitability of massive distress sales of long-term assets into a paralyzed marketplace.”

Who came to the rescue? The cause of the problem. “The gravity of the situation penetrated to an initially incredulous Federal Reserve,” Wojnilower continues. Banks were invited to borrow at the discount window in the face of “the very lively fears that major banks might have to close their doors.”

The shock of the credit crunch led the Fed into “a long-lasting series of private and public reassurances that no such crisis would ever be permitted to recur.” How did that work out? Three years later came the more severe credit crunch of 1969. As economist Charlotte E. Ruebling wrote at the time, “market interest rates have soared to levels never before reached in this country,” but “rates on deposits at banks and other financial institutions have been held much lower.” By the Fed, of course.

The authors of Regulation Q had a really bad idea, based on the false assumption that the Fed would somehow know the right answer. But the Fed did not know what the right interest rate was in 1966, or 1969—nor do they know it now. They never have and cannot know it. Put not your faith in their dubious “expertise.”